(Hair)

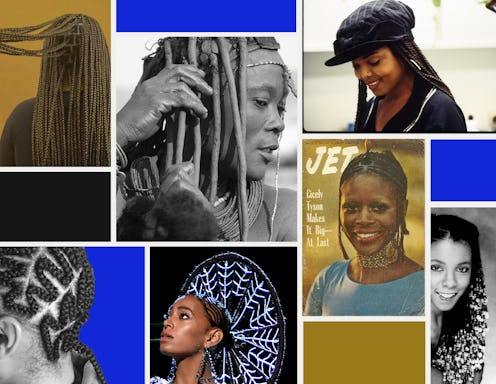

How The Tradition & Meaning Of Braids Evolved Over Time

And where it stands now.

Although hair braiding is a hairstyle found throughout cultures, the practice holds a revered place in the Black community. As Black people have voluntarily and involuntarily moved throughout the world, the specific culture of hair braiding has transformed to reflect the impact of history and communal change. What began as an extension of ancestral customs has evolved into tools of survival, functionality, community and even artistic expression. Here, we look back on and celebrate the history of hair braiding as well as its future.

Traditional African Hair Braiding

Beautification practices in Africa vary in meaning across countries, cultures, and tribes. In many cases, hair braiding was and continues to be used to express information about the wearer including marital status, age, spiritual connections, or tribe.

The nomadic Himba tribe in northern Namibia are known for their grooming practice of covering their skin and hair in a red, aromatic paste called Otjize that has cleansing, UV protective, and spiritual properties. The accompanying braiding traditions are nuanced, differing between clans and indicating highly specific information. Long, individual braids covered and sculpted by Otjize and topped with a headdress are common amongst women to mark fertility and marital status. Simpler braids are worn by children and become more elaborate with age.

Many braiding traditions, like those of the Himba tribe, thrive today while others have waned with time. Particularly, modern-day hair braiding in the United States is largely led by zeitgeist rather than cultural messaging. Still, braids have earned additional purpose throughout Black history maintaining a larger impact alongside a function of beauty.

Braids As Community & Resistance

Stories of enslaved Africans hiding rice, grain and other items within braids during the Middle Passage and when escaping demonstrate how braids became part of survival. Many oral history accounts claim certain braided styles served as wordless communication of who was ready to escape or mapped routes to safety. “[Braids] signify our intergenerational ties. They signify the African-ness in us that would not die in the process of coming to this country,” says interdisciplinary artist Shani Crowe who often uses large-scale, intricate hair braiding in her work to celebrate Black beauty. “Braids have been used to preserve even the agricultural parts of our culture.”

The power to facilitate connection is a characteristic of hair braiding that’s held throughout Black history. Hair braiding has always been a social activity entrusted to family or skilled community members and ultimately deepened relationships. “In my personal experience, I was definitely sitting on the floor, between somebody’s knees getting my hair braided on the porch or in the kitchen,” Crowe recalls. “You spend a lot of time with someone when you braid hair so you develop relationships with people.” The communal aspect of doing hair offered opportunities for Black people to build lives in America and resist oppression. “Madame CJ Walker and other Black hair entrepreneurs created spaces where a lot of Black revolutionaries and leaders were able to gather,” says Crowe. “They got that space from the money they made beautifying other women.”

Today, African hair braiding shops, particularly in New York’s Brooklyn and Harlem boroughs, similarly sit at the intersection of community and beauty service. “There’s just something about the salon atmosphere that makes you feel at home,” says celebrity hair braider Helena Koudou who’s worked alongside her family at Alima African Hair Braiding Salon in Brooklyn since she was 15. “[My aunt’s salon] has been in the neighborhood for more than 20 years. She has known people from when they were young. She used to throw cookouts and would invite people to eat. So she made it a home for who comes in and out. I try to do the same with my clients.”

Braids Through The Years

Although racist policies and social norms placed premiums on straight hairstyles, natural hair returned en vogue during the 1960s and 70s. The Civil Rights and Black Power Movements encouraged natural hairstyling as a political statement — braids included. Most notably, actor Cicely Tyson is regarded as the first Black celebrity to sport natural hair for mainstream television and cinema. Tyson wore a braided style reminiscent of the now popular Fulani braids on the March 1973 cover of Jet Magazine and again for various movie promotions and portraits. She received both praise and backlash but continued to subvert beauty expectations by regularly wearing her natural hair throughout her career.

Braids of choice during the 1980s reflected the high-impact vibrancy of the decade. Braided bobs replete with bangs and braids packed with colorful beads or other ornaments were popularized by musicians like Patrice Rushen and Rick James.

Black celebrities, musicians and iconic pop culture moments would continue to set off new braid trends. Janet Jackson’s influential role in the 1990s drama Poetic Justice breathed new life into long, box braids and inadvertently renamed them. “I remember people kept coming in and asking for Janet Jackson braids and my mom and aunt would look at me and be like, ‘What is that?,’” says Koudou. “These styles have always been around. They just have a new name.”

The early 2000s saw the rise of various microbraid trends. The extremely skinny, individual braids are beloved for their versatility and resembling the look of naturally flowing hair. Actor and singer Brandy was known for wearing microbraids in her popular roles as Moesha and Cinderella. The characters deeply resonated with young Black viewers’ at a time when Black hairstyles were not widely accepted. “Seeing [Brandy] in Cinderella with braids — I wanted my hair just like that,” says Danielle Washington, beauty brand consultant and former co-founder and chief marketing officer at plant-based hair extension brand Rebundle. “Seeing braids in the media around that time, for me, was important.”

Crowe, Koudou, and Washington agree that knotless braids are currently the most popular style. The specific braiding technique uniquely eliminates the need to secure extensions at the root with a visible knot. “[Knotless] looks more natural,” says Koudou. “The styles went from ‘oh she has extensions in her hair’ to ‘I can’t tell if that’s her hair or not.’” Knotless braids’ seamless finish transformed braids from a functional decision for vacations or to protect damaged hair into a fashion-forward look. “In my childhood, braids were often pitted against straight hair,” says Washington. “[Braids] definitely served that functional need but with the knotless aspect we remembered that, ‘wow, this is sexy.’”

The Future of Braids

Recent shifts in societal perceptions of Black hair have made room to further embrace braided hairstyles. The passing of the Crown Act in 2020 officially made discrimination based on hair texture illegal, a move that largely protects Black people from workplace disenfranchisement. “The type of braiding I was doing when I created the show BRAIDS — I had to take all that stuff down after,” says Crowe of her viral 2016 exhibition featuring avant-garde braided sculptures that caught the eye of Solange. “The models had to go to work after.” Now, braiders are noticing clients taking more risks with their hair. “I have a few clients, not a lot, but a few clients who love to experiment with different hairstyles,” says Koudou. One of these hairstyles takes inspiration from Cicely Tyson’s iconic braided crown pinning braids in circles at the forehead to resemble curled bangs with a tall, tight topknot. “When [people] see somebody do that they’re like ‘oh, that’s fine. I want to do that too.’”

Similar to changing tides amidst braid trends, the braiding hair used to create these styles is experiencing an overhaul. Hair extensions have a reputation for harmful production methods. Synthetic hair is typically coated in skin-irritating, health-concerning chemicals while human hair harvesting can be exploitative of vulnerable donors. Personal care products marketed to Black and brown consumers are already more likely to contain potentially harmful ingredients, revealing blind spots in the beauty industry's growing clean initiative. “The systemic nature of the hair extension industry is taught and passed down,” says Washington. “It does not start with Black people but it definitely ends with it.”

The hair extensions industry is growing quickly and is expected to reach almost $5 billion by 2032, making manufacturers resistant to profit-threatening innovation. However, disruptive brands like Rebundle are forcing a change of guard. Rebundle is the first-ever producer of plant-based, recyclable hair extensions that are safe for both the wearers and the environment. They also offer a recycling program for consumers to mail back competitor extensions, placing additional pressure on the industry to catch up. Rebundle recently raised $1.3 million in growth funding, demonstrating a community and industry hunger for something better for Black beauty consumers.

Throughout history, braids have played a constantly evolving yet always critical role in the lives of Black people. The practice has preserved culture, built community, helped resist oppression and served as a medium of self-love. As the full breadth of braids becomes increasingly venerated, we can expect creativity to continue blossoming.

This article was originally published on