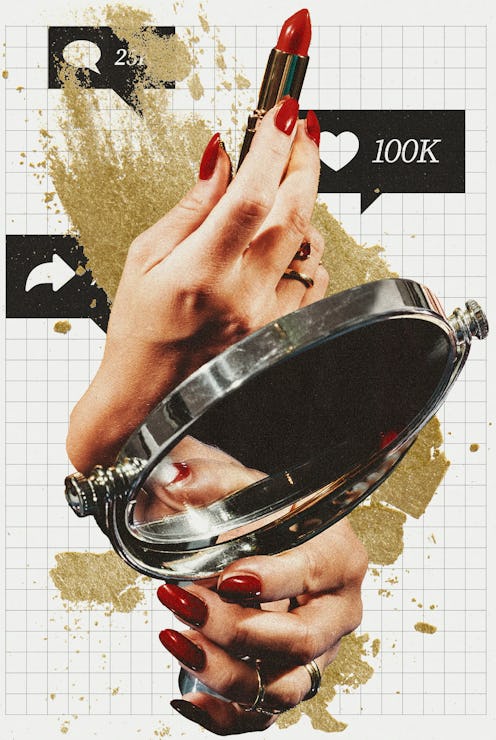

(Makeup)

A Viral Beauty Product Is No Guarantee You’ll Actually Get Results

Unpacking the industry’s buzziest term.

Language is a funny thing, isn’t it? Because of the speed at which culture evolves, trends emerge, and as a result, there are often words that enter our everyday lexicon that don’t have a concrete definition, but we mutually understand. Or do we? The word “viral” is commonly thrown around in the beauty industry, but does anyone actually know what it means when it’s used to describe products? Maybe in theory, but the exact metrics behind it are murky.

It’s reminiscent of the famed 1964 case Jacobellis v. Ohio, revolving around the definition of “obscene.” When Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart was asked to describe his definition of obscenity, he couldn’t quite define it, so his answer? "I know it when I see it."

What is clear is that today's beauty consumer is smarter than ever. They are more educated about the active ingredients in their skin care, the sustainability practices of their favorite brands, and the founders that they’re buying from. In the last decade, even the last five years, there has been a palpable shift in the way trends emerge, moving away from brands telling consumers what they need to customers demanding to know exactly why they should purchase a product.

To make a sale, brands need to cover all of the aforementioned bases (and then some). The reality is many marketing and PR departments are just not equipped to answer all of these questions due to a variety of internal factors, including outsourcing various aspects of the production process and a company-wide education on the specific ins and outs of their goods.

There are no shortcuts to selling a product. That is, until you wave what seems to have become a magic wand: going viral.

What Does “Going Viral” Actually Mean?

A viral product is one that has become an overnight success, thanks mostly to a rise in popularity on social media. Virality is covetable because a brand’s product is organically introduced to a wider audience at no cost. But the term “viral” isn’t a concrete destination that can be measured by sales or dollar signs. So why are so many brands banking on a status that has about as much staying power as lip gloss?

Laura Pitcher, a Brooklyn-based NYLON writer who focuses on the intersection of fashion, beauty, trends, and culture, says, “At the moment, people are skeptical of brands and are bored of traditional advertising so they want their product recommendations from actual people instead. Unfortunately, once brands try to cash in on this shift and force virality, it ruins the magic of organic recommendations.”

Part of the magic of virality is that it is completely unpredictable. Yes, every brand wants all of their products to be runaway successes, but a product going viral is completely happenstance. It’s an alchemy of what’s on trend, the current cultural landscape, and more than anything, a little luck.

Despite the beauty industry’s hyperfixation on newness, a viral product doesn’t have to be a new one. It’s not unheard of for an under-the-radar item to pop off on TikTok and suddenly become the brand’s biggest seller of the year (Clinique's Almost Lipstick in Black Honey is one example of this). However, like any overnight rise to fame, as quickly as it’s given, it can and will be eclipsed by another product.

Virality Throughout History

Prior to TikTok, the advent of YouTube beauty culture in the early 2010s birthed the earliest iterations of the influencer, and gave us the first instances of the viral phenomenon. Products became essential when NikkiTutorials deemed the OFRA Highlighter a must-have, MannyMUA used Tarte’s Shape Tape Concealer, or seemingly everyone on Earth used Urban Decay’s Naked Palette.

Since the trends didn’t always turn over once a week like they do today, thanks largely to social media algorithms, these products would often sustain their popularity for much longer. This is why we look back and often see products directly tied to eras in beauty. The mid-2010s are defined by products like Anastasia Beverly Hills Dipbrow, Kylie Cosmetics Lip Kits, and Too Faced Better Than Sex Mascara, rather than quickly-changing trend monikers of 2023 like Barbiecore, Tomato Girl, and Quiet Luxury.

Today, virality as we know it is due largely in part to TikTok, and the ripple effect that it creates. The earliest instances of this modern phenomenon were seen with PHLUR’s Missing Person, Dior Rosy Glow Powder Blush, Rare Beauty Liquid Blush, and Cloud by Ariana Grande. After the beauty industry as a whole saw the unprecedented success of these favorites, the concept of a “viral” turned from a happy accident to a key performance indicator.

In the same way you can’t pinpoint the definition of virality, you can’t fake it. Yet the data by which we measure the popularity of a product or trend is murky. Sellout rates, repeat purchases, copycat products, and of course, ubiquity on social media tend to all point to a product becoming its own moment.

If you’re online at all, you’re probably familiar with Glow Recipe, the “fruit-forward” skin care brand in eye-catching, fruit-shaped packaging that’s designed to be scroll-stopping on social media. The brand has gone viral many times in the last few years, not only because their stuff is aesthetically pleasing and made for Instagram, but because the products really work. But as co-founder Christine Chang will explain, they don’t bank on virality, they invest in community, and let their fans naturally show what they love. “Virality isn’t just about a single creator creating a piece of content that has garnered millions of views, but when our entire community rallies behind a product or educational hack,” says Chang.

She continues, “Over the years, we’ve built a super engaged community where they’re often posting about a new product even before it has launched. While we don’t plan for virality, engaging and involving our community has always been part of our brand ethos — from testing formulas, digestible clinical ingredient education, to getting the opportunity to be the first to receive our newest launches. We believe this has naturally led to buzz-worthy moments and conversation on social.”

The State of Viral Beauty Products In 2023

Because virality is difficult to define, brands have been playing fast and loose with the term. Suddenly, everything is viral. But if everything is viral, is anything?

Darian Harvin, an LA-based beauty editor who covers beauty’s intersection of pop culture and politics, is skeptical. “I think the word ‘viral’ has lost its meaning because of where it's used today — everywhere,” she says. “It's a word we now gloss over as consumers because we are, in fact, over-familiar with it. We know what it looks and feels like thanks to algorithms that help to shape what's viral. Virality, it's really something you can’t state. It's a feeling one creates — and it's hard to manufacture.”

Regarding today’s landscape where it feels like everything has achieved this coveted status, Pitcher counters, “I think a lot of the products that brands advertise as being viral have only really gone ‘baby viral’ or have just been posted by one or two influencers. To me, I know something is viral when my mom has seen it.”

Why Going Viral Holds Weight

Like “clean beauty” and “genderless beauty” before it, virality is the newest buzzword that beauty brands are capitalizing on without ever having to back it up. So why does it matter if a product is selling out or not?

Jonah Berger, Wharton professor of marketing and bestselling author of Contagious, explains, “Some of this is about social proof. Products are popular, it makes other people more likely to buy them, or get interested in them, so as a result, companies are marketing their stuff as viral in the hopes that other people will be more likely to buy and use them.”

Why would a brand want to go viral? Jordan Samuel Pacitti, founder of Jordan Samuel Skin and a skin care industry expert, explains, “It certainly benefits a brand when a product receives a ton of attention through posts, likes, and shares, which creates a moment for both the product as well as the brand as a whole. However, [the downside of going viral is that it] can lead to … their newly acquired customers jumping on trends without doing their due diligence to research if the product is truly right for them.”

The Downsides Of Buying Into Virality

Just because a product works for the majority of influencers praising it online doesn’t mean it’s right for you. Pacitti explains, “Purchasing a product because it has gone viral is no different than playing the lottery. The chance of winning is very unlikely, while the chances of the product becoming another item that is added to the customer’s ‘product graveyard’ are very high.”

Pitcher points out that products reaching this cult status can introduce consumers to a luxury formula found at an accessible price point, but echoes the aforementioned point that too much of anything will often lead to waste.

“One plus I would say about online virality culture is that this can mean that more affordable alternatives can get the spotlight,” she says, “but the overall obsession with virality obviously encourages overconsumption.”

While it’s hardly fair to say that buying a blush is directly fueling the climate crisis, it is important to look at how marketing trends aim to affect our purchasing habits. Understanding that beauty generates 120 billion units of packaging per year, the sheer numbers become a sobering reminder that newness isn’t always the best reason to buy.

Why We’re Influenced By Viral Products

Virality itself is not the problem. Trends are exciting, popular products are great, and yes, every once in a while, buying a new beauty product feels good. Sometimes, capitalism does make some points. It’s when brands commandeer a term that was never theirs to begin with that it begins to become grating. Virality should be exchanged between consumers, beauty enthusiasts, and fans, in order to share what they love with their community and help others discover a product they might love, too. The bottom line is that when a brand releases a new launch, it should be good enough to stand on its own without the boost of momentary internet fame.

So, why does the popularity and ubiquity of going viral even matter? Are we doing it for ourselves, each other, or our social media followers? In beauty, the line is often blurred because using products is both a solitary and communal experience. Yes, we put makeup on for ourselves, for many different reasons, but we can’t ignore that it directly affects the way that we’re perceived as we move through the world, no matter if we care or not. So, what draws us humans to all want to wear the same blush, smell like the same fragrance, or use the same mascara?

Berger explains, “We often look to others to figure out what the right thing is to do, so people often take the fact that something is popular as a signal that it must be good. In addition, while people do like standing out, they also want to fit in. They don't want to be the only person doing something, and if lots of other people are doing something they don't want to be left out, so they may hop on the bandwagon and do it as well.”

What’s The Solution?

So what is the antidote to virality? It’s easy to simply say stop shopping altogether, but it's more beneficial to be realistic. Earlier this year, there was the well-intentioned “de-influencing” movement on TikTok that attempted to deprogram viewers’ craving to be a part of every new release and show that there are flaws and shortcomings to every product, but it only seemed to confirm Pacitti’s earlier point, that every launch won’t be universal for every skin type, hair texture, and makeup preference. More so, a number of videos by creators talking about de-influencing went viral, which is counterintuitive to the original point of shopping your existing beauty closet.

Many people have started to do a “shop my shelf” angle, where they’ll mine their own beauty collections for products they have purchased but may have forgotten about. This reintroduces them to perfectly good products they already own, reignites their original excitement about them, and encourages them to use what they already have, and in turn, save money and reduce waste.

“Just like old-school TV ads or infomercials wanted to make you feel like if you didn't buy the product today, you'd be missing out, we can get caught in a loop of trying to keep up with the latest viral product,” Pitcher points out. “Once it starts flying off shelves, the desire to buy it only becomes stronger, but the truth is it's impossible to ever fully ‘keep up’ because companies have designed it to feel that way. Keeping us on the ‘virality’ treadmill is strategic — being satisfied doesn’t drive sales.”

This article was originally published on