(Love, Your Way)

Your Trust Issues Could Be A Sign Of This Common Attachment Style

Break those bad habits.

In relationships, fulfilling your needs and wants as well as those of your partner is challenging to say the least, especially when everyone is bringing their own learned behaviors and baggage to the table. These personal and nuanced experiences shape how one interacts with another, leading to a specific attachment style that may not always match that of one’s partner. That’s why it’s important to understand these patterns in oneself (and one’s partner) to not only better communicate and satisfy each other’s needs but also set the relationship up for long-term success.

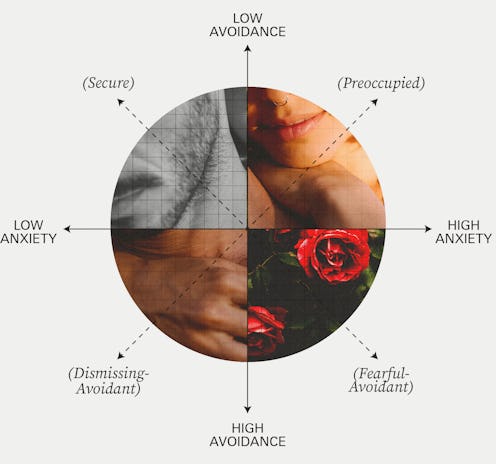

But where does one even start? Well, it might be helpful to first identify your relationship pattern, which is where the concept of attachment theory comes in. Attachment theory was first formulated by British psychiatrist John Bowlby some 60 years ago, and it essentially categorizes the common connection styles developed among humans into four primary buckets: secure, anxious, avoidant, and anxious-avoidant. “Attachment styles are the ways in which we interact with others through our thoughts, behaviors, and feelings,” Dr. Beth Pausic, clinical psychologist and director of therapy quality at Hims & Hers, explains to TZR. Coming to understand one’s own attachment style can shed light on how you connect with those you’re intimately involved with and also expose your biggest fears and hangups when it comes to relationships. “Bowlby believed that when we develop these styles in infancy, they become an internalized mental representation or model of what a relationship looks like [as one reaches adulthood],” Pausic adds.

Consequently, these internalized mental representations of oneself impact those we are dating and vice versa, particularly when conflict arises and needs are not properly met and communicated. Fortunately, that can be improved upon by researching one’s attachment style, seeking therapy, building self-awareness, learning strong communication skills, and establishing one’s own boundaries (and respecting the boundaries of others).

Amy Morin, Licensed Clinical Social Worker and Editor-in-Chief of Verywell Mind, tells TZR, “Attachment styles can shift over time. Most notably, people who struggle with attachment can learn to become securely attached with stable relationships and hard work [as it’s crucial to maintain healthy relationships].” Working on one’s attachment style as a couple is another great way to improve one’s behaviors with one another, as well as the relationship. “You can choose couples counseling and work to change these patterns with your partner,” Dr. Pausic adds. Ahead, mental health experts reveal and break down beneficial ways to become better attuned and self-aware of your attachment behaviors while dating.

Secure Attachment Style

“Secure attachment style is one in which the individual is able to form loving and secure relationships with others, marked by the ability to trust, give and receive love, have a general ease in developing relationships, and not be fearful of intimacy,” Dr. Pausic explains. These individuals typically grew up with a dependable, expressive caregiver. This attachment can also be formed from experiences later in life with self-work and therapy. “There is low anxiety and low avoidance of others.”

Individuals who form secure attachments tend to navigate issues easier than those with an [insecure] attachment, thanks to a healthy amount of self-esteem, the ability to form stable connections, and a willingness to open up and trust the other individual. They’re able to communicate their needs while respecting their partners’. “Couples with this attachment style are able to manage conflict and remain supportive and loving,” Pausic communicates. “There is an ability to manage emotions, respect differences, and communicate feelings [effectively].” Morin agrees and elaborates, “They can handle conflict and disagreements in a healthy way because they trust the other person is going to want to continue the relationship, even if they disagree on something.”

Anxious Preoccupied Attachment Style

Trust issues and low self-esteem often contribute to an individual’s anxious preoccupied attachment style (also known as anxious-ambivalent) — frequently creating “people-pleasing” tendencies and a need for constant reassurance. “They often worry that other people don't want to be close with them,” Morin shares. This behavior can often be learned from a caregiver’s inconsistent, mercurial attention throughout childhood. Typically, these individuals highly desire intimacy but tend to overreact to their partner’s behavior when a conflict arises. “Due to this fear, these individuals may be very needy in relationships and seek validation that they won’t be abandoned. There is high anxiety and low avoidance of others,” Dr. Pausic explains to TZR.

“A specific example of this style in a relationship is not getting a text back from your partner and automatically assuming worst-case scenarios, such as, ‘they don’t care about me,’ ‘they are leaving me,’ ‘they are cheating on me,’” Pausic states. This may instigate unnecessary fights, a constant need to talk or discuss feelings, and/or a desire to “test” or punish their loved one. If left unchecked, it can sometimes manifest into controlling or jealous behavior. “This [anxious behavior] reinforces their belief that they're not good enough or that others will abandon them,” Morin stresses.

Dismissive-Avoidant Attachment Style

“A [person with] dismissive-avoidant attachment style may seem aloof, which could drive people away, reinforcing the individual’s belief that they can't count on anyone,” Morin explains. This can often be traced back to a non-empathetic and insensitive caregiver, which may have left the individual feeling betrayed or disappointed as a child. In adulthood, this causes emotionally distant behaviors and a tendency to put up walls in relationships as a form of self-protection. “These individuals tend to have low anxiety and high avoidance of others,” Dr. Pausic points out. They struggle with deep intimacy beyond the surface level and often find ways to drift from their partner when conflict arises. Individuals with this attachment style value independence to an extreme degree, require a lot of space, and ample “alone time.” The “emotionally unavailable” types, if you will.

However, people with this attachment style do desire connection but struggle with managing their emotions, due in part to their grapples with trust. For example, they may even perceive their loved ones as “clingy” when they very well may not be, while potentially pushing those away from getting close to them — frequently out of the expectation of being let down. “They're usually comfortable without having close relationships and don’t want anyone to depend on them,” Morin explains. “They tend to hide their feelings, and if they feel rejected, they distance themselves from the people who are rejecting them.”

Anxious-Avoidant Attachment Style

A combination of the previously mentioned insecure attachments, “an anxious-avoidant attachment style (also known as fearful-avoidant to disorganized attachment) often presents confusing behaviors,” Dr. Pausic points out. “The individual both fears and craves connection.” Often, it is attributed to a hostile caregiver growing up and/or due to unsettled traumas, sudden life changes, or sudden loss. “They alternate between not trusting a partner and wanting reinforcement and validation. It may be difficult for them to regulate emotions, and they tend to have poor boundaries. There is high anxiety and high avoidance.”

This oxymoronic behavior, also known as the “come here, go away,” mentality, enables potentially toxic interactions with their partner. “They may seek less intimacy from others and might suppress their emotions,” Morin adds. Others involved may feel deleterious from this conflicting behavior, and those with this attachment style tend to create a self-fulfilling prophecy indulged by their trepidations of getting hurt. Ghosting someone as a protective mechanism from potential rejection that hasn’t even occurred yet is one example. They tend to disclose their feelings and fears while simultaneously pushing their partner away.

Evolving From An Insecure To A Secure Form of Attachment

As mentioned previously, attachment styles can shift throughout one’s life, so being keenly self-aware of how your strengths and limitations impact your relationships is key to achieving and maintaining a secure form of attachment.

Jenny*, a dance teacher based in Los Angeles, says she previously exhibited an anxious attachment after being involved in a tumultuous relationship with an avoidant individual. “When I was with my ex, and there was conflict, I would handle it by wanting to talk about it ASAP, and he would want to just shut down, usually for a couple of days, with very limited communication,” she recalls. “He emotionally hibernated (but wasn’t even able to communicate that that’s what he needed).” This avoidant behavior just fueled Jenny’s anxiety and need to contact her partner even more. Morin notes that this is common with anxious and avoidant pairings.

“When we did finally talk about the conflict, no matter how big or small, it usually felt like nothing was ever truly resolved or that a plan for change was ever agreed upon,” Jenny adds. The relationship eventually ended, and the dance teacher discovered attachment theory and came to terms with her own patterns of behavior through therapy. These days, Jenny is in a relationship with a securely attached partner. “I’m now able to better catch triggers that activate my old anxious habits,” she says. “I utilize self-talk to remind myself of things I know to be true, and [take comfort in knowing] my current boyfriend values me. I always picture a child who has recently learned how to ride a bike without training wheels, and I am newly on my ‘big kid bike’ of secure attachment.”

Xander*, an actor based in Los Angeles, similarly evolved from anxious attachment style, which was rooted in behaviors learned as a child. “Being raised in an environment where my father was short-fused created a people-pleasing tendency, that was a means to gain love and approval.” This then carried over into adulthood. “I still felt very socially anxious. It was hard to approach women and I didn’t have a serious girlfriend until my mid-twenties.” This led to a series of unhealthy relationships, particularly one with an anxious-avoidant individuals that was detrimental to his health. “It didn’t seem like she was aware of her behaviors [towards me] nor wanted to take responsibility for how it negatively affected me.”

After that relationship ended and he sought help through therapy and self-work, Xander began to combat his insecure attachment by setting boundaries and effectively communicating his needs. “I learned to voice my feelings and needs when [specific] triggers popped up.” Finding a partner with a secure form of attachment also proved beneficial in exemplifying what a healthy connection can and should look like, he says. “She was thoughtful, caring, and transparent,” explains Xander. “It was easy to build a secure relationship with her because of her own behaviors towards me.”

The takeaway? Keep working on yourself. “I’m dedicated to doing the hard work, including recognizing my own faults, owning them, and having a strong support system around me to hold me accountable when I want to act in an anxiously attached manner,” says Jenny. “It has slowly but surely changed my way of thinking and my emotional and mental reactions to things.”

Xander seconds this notion, adding that his biggest takeaway is that you and only you are responsible for getting your needs met and protecting your emotional wellbeing. “Remove the expectation and assumptions,” he says. “Some people are more in tune than others, and in those moments, it’s important to make sure you communicate your needs in a healthy safe way, so you feel fulfilled, safe, and secure in your relationship [or know when to walk away if you don’t].”

*Last name has been omitted for the sake of anonymity.

Studies and Books Referenced:

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss, Vol. 1: Attachment (p. 194). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Van Rosmalen, L., Van der Veer, R., Van der Horst, Frank (2015, May 9). Ainsworth's Strange Situation Procedure: The Origin Of An Instrument. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbs.21729

Benoit, D., MD FRCPC (2004, October 1). Infant-parent Attachment: Definition, Types, Antecedents, Measurement and Outcome (Vol. 9, Issue 8, pp. 541-545). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/9.8.541

Lee, A., Hankin, B. L. (2009, March 12). Insecure Attachment, Dysfunctional Attitudes, and Low Self-Esteem Predicting Prospective Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety During Adolescence (Vol. 38, Issue 2, pp. 219-231). Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15374410802698396

Ein-Dor, T., Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P.R. (2011, January 20). Effective Reaction to Danger: Attachment Insecurities Predict Behavioral Reactions to an Experimentally Induced Threat Above and Beyond General Personality Traits. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550610397843

Ainsworth, M. D. & Bell, S. M. (1970), Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development (pp. 41, 49-67).

Levine, A., Heller, R. S. F.. (2010, December 30). Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It Can Help You Find — and Keep — Love. Penguin Publishing Group.